Picture by Picture – Frame by Frame: Animation from Germany

Contents

- Animation

- From drawn movement to animation

- The animated film is being created

- Puppet animation and its development

- Innovations in puppet animation

- New paths

- The cut-out animation film

- Cut-out animation technique in the GDR

- Cut-out animation in the Federal Republic

- Cartoon animation

- Variations and creative approaches

- Cartoon animation in Germany before 1945

- Cartoon animation at the DEFA Studio for Animated Films

- The post-founder generations at the DEFA animation studio

- Animation in the FRG

- Manipulated puppets in film

- Manipulated puppet films for DEFA and television

- New paths in manipulated puppet film

- Silhouette animation

- Silhouette animation at DEFA

- Silhouette animation in the Federal Republic of Germany

- Animation studios in the two German countries

- The DEFA Studio for Animated Films

- The animation studio of East German television

- Our Little Sandman and The Little Sandman

- Aspects of animation dubbing in Dresden

- The impulse process

- The Subharchord

- Animation unit

- Computer animation

- Computers and artifacts

From drawn movement to animation

The word animation is derived from the Latin “anima” (soul). It refers to an artistic method of creation that transfers human characteristics and behaviors to objects and makes them visible. Animation in the sense of animating or enlivening things is part of artistic thinking, but for several thousand years it could only be represented in literature. It was only through the artificial creation of movement by means of film that pictorial representation became possible.

“Normal” (i.e. live-action) film shows movements that actually take place in reality. However, the classic manual animation techniques still used today — puppet animation, cartoon animation, cut-out animation, and silhouette animation — create the image movements “virtually.” In animated films, therefore, no movement is “recorded”; instead, the illusion of movement is created from inanimate objects or drawings. This animation is traditionally achieved through frame by frame recording and thus through phase design. For one second of film, usually 24 individual frames must be recorded.

The animated film is being created

Around 1906, a filming technique known as “stop motion” (German: “Stopptrick”) is developed. The camera is stopped during filming and resumes running after changes have been made to the set. The resulting effect is later developed into single-frame recording. The slight changes that occur in the process use the afterimage effect of the eye to create an illusion of movement using mechanical or electronic devices.

All manual techniques are based on this basic principle and differ only in the spatial dimensions of the materials used. The flat ones form the templates for drawing, cut-out or silhouette animation. Three-dimensional objects are used in puppet animation, as well as in the variants of clay animation or pixilation, i.e., the “animation” of living people.

In Germany, these techniques lead to a specialization of filmmakers and studios, very often in small-scale commercial structures. It is not until the DEFA Studio for Animated Films (lit., DEFA Studio für Trickfilme) is established in Dresden that a larger production facility is created by bringing together many different areas of animated film.

“Live-action film breaks down movement that exists in reality […] into individual images, which are then transformed back into movement in front of the viewer. cartoon and model animation, on the other hand, first creates the movement. Something dead and motionless is brought to life through it.”

(Arne Andersen, 1958)“Animation is not the art of drawings that move but the art of movements that are drawn.”

(Norman McLaren, 1950s)“The illusion of motion is created, rather than recorded.”

(Charles Solomon, 1988)

Puppet animation and its development

In puppet animation, three-dimensional bodies and objects made of various materials are brought to life through frame by frame animation. As “film actors”, these figures are subject to the laws of gravity. They must not change shape under their own weight or bounce during animation. Limbs and heads should be easily adjustable and allow for versatile mobility for the film in production. In the early years, the puppets are weighted down with sandbags to keep them in the desired position. These are attached to the feet and hung under the backdrop. Later, pins are used to fix the figures’ feet to a cork board.

Puppet animation initially also exists in Germany under the name “plastic animation”. The Berlin company “Plastrick” produces a good two dozen such films between 1921 and 1924. At the same time, the fairy-tale films of the Polish-Russian artist Ladislas Starevich enjoy increasing popularity throughout Europe. The Diehl brothers, based near Munich, are the best-known representatives of puppet animation in Germany before and shortly after the Second World War. Their “Mecki” character in particular caused a sensation. In the post-war period, Czech filmmakers such as Jiří Trnka and Hermina Týrlová have a particular influence on animated film in the GDR. Many characteristics of the figures used in the DEFA Studio for Animated Films in Dresden, such as typification and stylization, the four-fingered hand, and the immobile mouth, can be traced back to them. However, traditional frame construction remains the norm, as in the animated fable The Wonder-Working Doctor (Der Wunderdoktor, Herbert K. Schulz, 1957).

- [1] Rosemarie Küssner animates False Alarm (Blinder Alarm, Johannes/Jan Hempel, 1954) at the DEFA Studio for Popular Science Films (lit., DEFA Studio für Populärwissenschaftliche Filme) in Babelsberg; with Hans-Jürgen Berndt assisting as a “bag carrier”. ©DIAF/Estate Küssner, Schulz

- [2] Günter Rätz at the DEFA Studio for Animated Films in Dresden animating the episode The Sledge-Drive (Die Rutschpartie) from the mini-series Tales and Yarns (Schnaken und Schnurren, Johannes/Jan Hempel, 1956) based on the caricatures by Wilhelm Busch. ©DIAF

- [3] Robert Pfützner animates Proxima Centauri Adventures (Unternehmen Proxima Centauri, Jörg d’Bomba, 1962) at the DEFA Studio for Animated Films in Dresden. ©DIAF

Innovations in puppet animation

The experiments of Czech filmmaker Karel Zeman in the late 1940s were already influenced by modern international trends. His wire figures (Mr. Prokouk, presumably made of iron wire) are more flexible and lighter than the heavy metal frames. In the puppet studio of East Berlin’s television broadcaster Deutscher Fernsehfunk, annealed copper wire is used in the late 1950s. In the Dresden studio, director Johannes (Jan) Hempel uses lead wire in his feature-length film The Strange History of the People of Schiltburg (Die seltsame Historia von den Schiltbürgern, 1961). But it is the aluminum “wire men” developed in Dresden in the early 1960s that expresses the courage to embrace radical abstraction, as the figures act unclothed in a minimalist setting. Günter Rätz’s The Race (Der Wettlauf, 1962) brings the studio a major commission from the French television company CAP-Distribution for a more than 40-episode series revolving around its main characters Filopat and Patafil. Rätz now works almost exclusively with wire figures, but they are no longer naked, instead appearing imaginatively clothed, as in the animated musical The Lighthouse Island (Die Leuchtturminsel, 1979).

The experiments of Czech filmmaker Karel Zeman in the late 1940s were already influenced by modern international trends. His wire figures (Mr. Prokouk, presumably made of iron wire) are more flexible and lighter than the heavy metal frames. In the puppet studio of East Berlin’s television broadcaster Deutscher Fernsehfunk, annealed copper wire is used in the late 1950s. In the Dresden studio, director Johannes (Jan) Hempel uses lead wire in his feature-length film The Strange History of the People of Schiltburg (Die seltsame Historia von den Schiltbürgern, 1961). But it is the aluminum “wire men” developed in Dresden in the early 1960s that expresses the courage to embrace radical abstraction, as the figures act unclothed in a minimalist setting. Günter Rätz’s The Race (Der Wettlauf, 1962) brings the studio a major commission from the French television company CAP-Distribution for a more than 40-episode series revolving around its main characters Filopat and Patafil. Rätz now works almost exclusively with wire figures, but they are no longer naked, instead appearing imaginatively clothed, as in the animated musical The Lighthouse Island (Die Leuchtturminsel, 1979).

- [04] Ina Rarisch animating The Strange History of the People of Schiltburg (Die seltsame Historia von den Schiltbürgern, Johannes/Jan Hempel, 1961) at the DEFA Studio for Animated Films in Dresden. ©DIAF

- [05 — see right] Jörg Herrmann animates his film The Specialist (Der Fachmann) from the series Filopat and Patafil (Filopat und Patafil, 1965) at the DEFA Studio for Animated Films in Dresden. ©DIAF

- [06] Barbara Eckhold animates The Grand Celebration (Das große Fest, Werner Krauße, 1972) at the DEFA Studio for Animated Films in Dresden. ©DIAF/Siegfried Jung

New paths

In the 1960s, director Kurt Weiler and set designer Achim Freyer break new ground in puppet animation in the GDR. Both filmmakers drew inspiration from everyday materials and experimented with form and stylization. In Heinrich the Wannabe King (Heinrich der Verhinderte, 1965), for example, they even use interchangeable heads. In contrast, the 13 episodes of the series about the German-Czech mountain troll Rübezahl, which is released in 1975, breaks new ground in terms of organization as a co-production between the GDR and Czechoslovakia. In terms of set design and narrative style, however, they remain rather conservative. In the 1970s and 1980s, puppet animation continues to develop at the Dresden studio. The characters are increasingly equipped with movable mouths and faces. Walter Später’s clay animation (plasticine animation) also strove for more flexible character shapes.

Despite the triumph of computers, puppet animation films are still being animated manually worldwide today. In Germany, the series Our Little Sandman (lit., Unser Sandmännchen) and its bedtime stories Abendgrüße continue to rely on this technique. Internationally, successful studios and names such as Aardman Animations (UK), Claude Barras (Switzerland), Kristina Dufková (Czech Republic), and Adam Elliot (Australia) are beacons of this technique.

- [07] Kurt Weiler animates his film The Farmer and the Generals (Der Bauer und die Generale, 1960), his first collaboration with Achim Freyer, in the puppet studio of Deutscher Fernsehfunk in Michaelkirchstraße in East Berlin. ©DIAF/Weiler estate

- [08] Günter Rätz animates his film The Trace Leads to the Silver Lake (Die Spur führt zum Silbersee, 1989) at the DEFA Studio for Animated Films in Dresden. ©DIAF/Rudolf Uebe

- [09] Sabine Berger animates an episode of the Pondorondo series for the bedtime stories Abendgrüße at Sandmann Studio Babelsberg in 2005. (Sabine Berger, Ulf Klaudius; 2004–2007). ©Volker Petzold

The cut-out animation film

In 1909, Frenchman Émile Cohl creates an animated film featuring drawn matches as characters. This small work inspires Berlin-based cameraman Guido Seeber to make an animated film using real matches. He lays the matches on a flat surface and places the camera above them. Then he moves the matches and captures each position as a single shot on film. In 1910, he completed the film The Mysterious Matchbox (Die geheimnisvolle Streichholzdose). This arrangement later gives rise to the first animation table. Guido Seeber thus established with this “flat figure animation” the cut-out technique.

This technique actually uses “flat puppets”. The figures are usually made of painted cardboard, with their body parts, heads, and limbs cut out beforehand (cut-out animation). They resemble cartoon characters in appearance. Once the figures and backgrounds have been completed, the animation is created on the animation table using standard single-frame recording.

Cut-out animation uses reflected light or a combination of reflected light and transmitted light (i.e., light that shines from below through the layers of the animation table toward the camera). The movement of the figures is not as complex as in puppet or cartoon animation, as the figures lie flat on the playing surface. Figures only need to be created once, and the animator then moves them across a surface without changing their shape. This allows cut-out animation to progress quickly. Compared to cartoon films, cut-out animation does not offer such a wide variety of shapes and possibilities for change. This can make it seem monotonous in longer films. On the other hand, the combination with other techniques and the use of different materials such as collages or sand offer attractive effects, especially for visual artists.

Cut-out animation technique in the GDR

Cut-out animation is already used in German advertising films before the World War II, although rarely. In the 1960s, it gained importance in both German states. At the DEFA studio in Dresden, Kurt Weiler uses the technique for the first time in 1956 in the opening credits of the children’s puppet animation film The Stolen Nose (Die gestohlene Nase). In 1958, Johannes (Jan) Hempel uses the cut-out technique in several scenes in Petra’s Blue Dress. In 1961, Günter Rätz directs Mister Twister, the studio’s first film animated entirely in this technique, but it is banned and destroyed. It is not until 1964 that the director is able to bring his first cut-out story to the cinema with the children’s book adaptation Heinrich the Deer (Hirsch Heinrich). Other directors at the Dresden studio perfected this technique, including Jörg d’Bomba, Walter Eckhold, Otto Sacher, and Christl Wiemer. East German television broadcaster Deutscher Fernsehfunk employs cut-out animation since the 1960s, primarily in commercials, while children’s television begins using it more frequently in its bedtime stories Abendgrüße in 1975.

As early as the 1960s, Czech director Břetislav Pojar successfully exploited the three-dimensional possibilities of cut-out animation. At the DEFA studio in Dresden, Katja Georgi takes inspiration from his style. In 1974, she contributes to the 26-part international series Fairy Tales of the European Peoples of the International Animated Film Association (ASIFA) with Spindel, Weaver’s Shuttle and Needle (Spindel, Weberschiffchen und Nadel). Katja Georgi brings materials such as fabrics, wood, and stones to life to tell a story. Ina Rarisch also shows her love for filigree detail in the television commission The Turtle (Die Schildkröte, 1983). Another variation of cut-out animation is magnetic board animation, in which figures can be moved and fixed on a metal surface using a kind of magnetic rubber layer (“Magnigum”). When animation artists then form figures out of threads on such a board, they have used string animation.

Cut-out animation in the Federal Republic

In the Federal Republic of Germany in the 1960s, avant-garde artists such as Wolfgang Urchs and Jan Lenica bring cut-out animation back into the public eye. Helmut Herbst and Franz Winzentsen enriched this contemporary, socially engaged animation. They use, among other things, the collage technique of poster artist John Heartfield and experiment with Dadaist ideas. The film festivals in Oberhausen and Annecy (France) were particularly important forums for the artists. Other filmmakers such as Jochen Euscher refined the economically efficient cut-out animation technique for advertising, education, and entertainment as small freelancing businesses. One of the few permanent platforms for animated German children’s films is the early evening TV series The Little Sandmann (lit., Das Sandmännchen) with its bedtime stories, which very often feature cut-out and silhouette animation films.

Cartoon animation

Cartoon animation is the oldest and best-known type of animated film. It uses all graphic or painting techniques to create the illusion of movement through phasing. An infinite number of shapes and their transformations are possible, often in combination with other techniques. The basic principle is based on the separation of background and figures, as well as a further division into moving and stationary elements. As with any classic manual animation, 24 in-between frames must be recorded for one second of film.

Based on the storyboard, draft drawings are created on paper with the scenes of the future film and their settings. After sketching the character designs with basic movements and spatial positions, the draft drawings of the main phases are created. The in-between phases determine the exact sequence of movements. These two processes take place at the drawing board, which can be rotated to facilitate the drawing of vertical and horizontal lines. This is followed by contouring, the transfer of the pencil drawings to crystal-clear transparencies (cels) using ink. After coloring, where the ink drawings are filled in with color, the transparencies are filmed frame by frame on the animation table.

Variations and creative approaches

There are many variations of this technique, which are always determined by the artists. Animated pencil or ink drawings are also possible without the cumbersome classical procedure and can be created directly under the camera. Animated painting is particularly challenging. When working with impasto paints (such as oil paint), the structure of the paint material is included into the image. Figures or objects appear as if out of nowhere and can disappear again without a trace. The reduced animation enables a particularly effective way of working. The effect of deception is enhanced by dispensing with in-between phases or limiting the animation to individual figures.

Cartoon animation in Germany before 1945

Cartoon animation also dominates animated film production in Germany between the two world wars and beyond. In contrast to Walt Disney’s legendary feature-length films, the technique is mainly used in advertising in this country. Hans Fischerkoesen, Wolfgang Kaskeline, Werner Kruse, Paul N. Peroff, and Curt Schumann are well known for their work in this field. Many of these attractive advertising films are produced by Julius Pinschewer before he is forced to emigrate to Switzerland in 1933. There are also experimental works by the artistic avant-garde, so-called abstract or absolute films, for example by Oskar Fischinger. However, drawn animation is also used for entertainment and for children, as well as in teaching materials and the military. Even in the middle of the war, the National Socialists attempt to establish a central studio à la Disney, which fails miserably. Fischerkoesen does not participate in this project, but produces three successful entertainment films with his own company towards the end of the war: The Weatherbeaten Melody (Die verwitterte Melodie, 1943), The Snowman in July (Der Schneemann, 1943), and The Silly Goose (Das dumme Gänslein, 1944).

Cartoon animation at the DEFA Studio for Animated Films

In 1954, several alumni of the Burg Giebichenstein University of Art and Design (Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule) in Halle (Saale) develop the animated film The Story of the Piggy Bank (Die Geschichte vom Sparschweinchen) for the state-run studio DEFA in an advertising graphics studio in the city on the Saale. This group, known as “Wir Fünf” (The Five of Us), includes Helmut Barkowsky, Klaus Georgi, Otto Sacher, Christl and Hans-Ulrich Wiemer. Shortly thereafter, Lothar Barke, who was clearly influenced by the Disney style, joins the group. In 1955, they all co-found the DEFA Studio for Animated Films in Dresden. In 1957, Klaus Georgi’s plea for equal rights for all people in There Are No Blue Mice (Blaue Mäuse gibt es nicht) comes under suspicion of “formalism” and is subject to censorship. In 1960, Lothar Barke directs Alarm at the Puppet Theater (Alarm im Kasperletheater), one of the most popular DEFA animated films. Meanwhile, Otto Sacher initiates an animation class in Dresden in 1960 to train specialists and continues his drawing and cut-out animation work in the studio until it closes in 1992.

The post-founder generations at the DEFA animation studio

From the 1960s onwards, a new generation of artists emerges which continues the work begun by the “founders” of the DEFA animation studio. Among them are experienced talents such as Heinz Engelmann (He Hellerau), who had already been working in animation before the war, and Ernst R. Loeser, who had returned from exile in England. The accomplished animator Christian Biermann switches to directing and focuses on advertising films and commercial breaks. Sieglinde Hamacher is only able to see the premiere of her outstanding film Contrasts (Kontraste, 1982) after the studio closed due to censorship. Nevertheless, she continues undeterred with the production of her short, pointed parables. Lutz Stützner gains a foothold in the studio in the 1980s and proves his talent for comics and comedy with his pointed film jokes. Freelance artists Lutz Dammbeck and Helge Leiberg stand out with their poetic and provocative, disturbing cutout and drawn animated works.

Animation in the FRG

In the early Federal Republic, drawn animated film advertising accompanies the so-called “economic miracle” sparked by the Marshall Plan. Established representatives from the pre-war and war periods, such as Hans Fischerkoesen, Werner Kruse, and Curt Schumann, continue with new talents and new accents in technique and style. Schumann produces for Fischerkoesen-Film in his own West Berlin studio, foregoing his label. Kruse-Film scores a huge hit with Dresden-trained Roland Töpfer and his “HB-Männchen” known throughout Germany. After the first television advertising boom in the late 1950s with the popular “advertising break characters” (Uncle Otto, Sehpferdchen, etc.), stage designer and graphic artist Wolf Gerlach creates a new generation of advertising characters in 1963 for the newly established TV station ZDF – the “Mainzelmännchen”.

Curt Linda’s film adaptation of Kästner’s Animals United (Die Konferenz der Tiere, 1969) leads to the era of popular feature-length animated productions at the end of the 20th century.

Werner and the Wizard of Booze (Werner – Beinhart!, 1990) and The Little Bastard (Kleines Arschloch, 1997, Gerhard Hahn and Michael Schaack respectively) as well as The Little Polar Bear (Der kleine Eisbär, 2001, Thilo Graf Rothkirch) prove to be the last classics of the old school before the upcoming digital cartoon era.

Manipulated puppets in film

They often resemble animated characters and seem to be the outsiders among puppet films. However, marionette, hand and rod puppet films have a different technical basis and their own tradition. They are not animated but are recorded with a running camera instead. Yet they are not merely filmed puppet theater shot sizes, pans, and cuts follow cinematic rules. Compared to animation, such films are often cheaper and less complex to produce. In the 1940s, famous manipulated puppets appear in films of the Saxon Hohnstein puppet company. These works were produced by Schonger-Film in Berlin and Boehner-Film in Dresden. Today, manipulated puppet films are sometimes included in the “animated film” category at festivals. This is mainly because, due to their rarity, there is often no separate category for them, especially in feature-length format. Nevertheless, there are examples of masterful works worldwide.

Manipulated puppet films for DEFA and television

From the very beginning, the DEFA Studio for Animated Films in Dresden also produces manipulated puppet films. These are created by experienced puppeteers and directors working in the studio, such as Carl Schröder from Radebeul, the brothers Erich and Werner Hammer from Halberstadt, and Walter Später from Halle (Saale). In line with the studio’s social mission, these films are primarily intended for children. Among the works are the farce The Horse Thief from Fünssing (Der Roßdieb zu Fünssing, Carl Schröder, 1961) and the poetic animal fable Little Chicken Katrinchen (Das Hühnchen Katrinchen, Hans-Ulrich Wiemer, 1979). Various series with hand-animated puppets are also an integral part of German children’s television for decades. In 1957, the “Märchenwald” (lit.: Fairy Tale Forrest) series (Hans Schroeder, Erich Hammer) with humanized animal characters is launched on East-German broadcaster Deutscher Fernsehfunk. It is varied for different program slots until the broadcaster’s deployment in 1991. Kater and Häschen (lit.: Cat and Little Hare, also known as Mautz and Hoppel) as well as Herr Fuchs and Frau Elster (lit.: Mr Fox and Mrs Magpie) are probably the most popular.

New paths in manipulated puppet film

At the beginning of the 1960s, the DEFA Studio for Animated Films starts producing not only children’s films but also satirical works for adults on current grievances in the country. The source of ideas is the newly founded Dresden cabaret “Die Herkuleskeule,” (lit.: The Bludgeon of Hercules) which is the inspiration for, among other things, The Stone Age Legend (Steinzeitlegende, Herbert Löchner, 1965). As a biting satire on bureaucracy and the prevention of innovation in the GDR, it is only approved by the government under certain conditions. The rod puppet episode is also the last in the promising “Puppenkabarett” (lit.: Puppet Cabaret) series, which is subsequently discontinued.

In the 1980s, a new generation of GDR puppeteers causes a sensation at the DEFA studio with their radically unrestrained styles and astonishing effects. These artists include director Dietmar Müller with his collective from the State Puppet Theater in Dresden and, above all, Peter Waschinsky from the Neubrandenburg Puppet Theater. Waschinsky attracts attention with his grotesque interpretation of the Grimm fairy tale The Pack of Ragamuffins (Lumpengesindel, 1983), among others.

Silhouette animation

Silhouette animation uses the technical and creative features of cut-out animation. The key difference is in the lighting. As in shadow theater, it is used from behind or from below as backlighting. While still a student, Lotte Reiniger performs scenes from plays by William Shakespeare with her own shadow theater. She creates intertitles in a silhouette style for two silent films by Paul Wegener. Wegener refers her to the Institute for Cultural Research, which is committed to educational and public awareness goals. However, it is also an experimental animation studio with a professional animation table. There, in 1919, Reiniger produces the first artistically sophisticated film using the silhouette technique, The Ornament of the Loving Heart (Das Ornament des verliebten Herzens). In Potsdam, with the support of banker Louis Hagen, Lotte Reiniger makes the world’s first feature-length animated film, The Adventures of Prince Achmed (Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Achmed), between 1923 and 1926. She also publishes the essay “How I Make My Silhouette Films.”

Silhouette animation at DEFA

In Halle (Saale), Bruno J. Böttge works as a camera assistant at the DEFA studio’s branch office for popular science films. He is given two home movie copies of Reiniger films and a 1924 cultural film book containing the artist’s article. He never met her in person. He enthusiastically uses this essay as a guide. Secretly after work, he shoots rehearsals and later gets the opportunity to create further short studies in silhouette animation on a small budget. Although these are never published, they lead to a commission for a fairy tale film using this technique. The Wolf and the Seven Little Goats (Der Wolf und die sieben Geißlein) is released in cinemas in 1953. Bruno J. Böttge is one of the founders of the DEFA studio in Dresden, where he establishes the silhouette division. He pursues two creative paths: the classic one after Reiniger and the modern one, reflecting international developments. He also passes on his knowledge to others such as Manfred Henke, Walter Eckhold, Marion Rasche, Horst J. Tappert, and Jörg Herrmann, the latter of which anchors this animation technique in digital production.

Silhouette animation in the Federal Republic of Germany

Despite the great admiration for Lotte Reiniger in Germany, her work hardly finds any continuation in this country – with two exceptions: One is the DEFA Studio for Animated Films in Dresden. The other is director and producer Herbert K. Schulz in the western part of Germany, who is particularly committed to silhouette animation. He is also a co-founder of the animation studio in Dresden, where – during his time as a puppet animation director – he certainly looks over Bruno J. Böttge’s shoulders. At the end of 1960, he leaves the GDR. With his West Berlin-based company cinetrick, Schulz produces eleven silhouette animation series with a total of around 100 short episodes for the “West Sandmännchen” (West German version of the Sandmännchen series) between 1963 and 1968. These include poetic, imaginative, and sometimes magical everyday stories, original interpretations of fairy tales, and even a western parody. Working alongside Schulz are the painter Hella Rost and the graphic artists Pepperl (Franz Joseph) Ott and Jean-Pierre Noth, among others.

The DEFA Studio for Animated Films

The DEFA Studio for Animated Films in Dresden is considered the most important producer of animated films in divided Germany. It is founded in Dresden in early 1955 in the former restaurant destination and dance hall “Gasthof Reichsschmied” in Ober-Gorbitz, which the advertising film producer Boehner-Film had already converted into a studio in 1938/39. It uses almost all of the animation techniques known at the time and even cultivated hand puppet films. Over a period of 47 years, the studio produces more than 1,500 animated films, mainly for children’s programs in GDR cinemas. Advertising and educational films for adults are also part of the production program. The company counts up to 250 permanent employees and numerous freelancers.

Despite dedicated rescue efforts, the DEFA animation studio is liquidated by the Treuhand trust after 1990. However, former employees are able to continue the Dresden animation tradition with their own companies and, to this day, bring productions from the region to international recognition. The German Institute for Animated Film (lit., Deutsches Institut für Animationsfilm, DIAF), founded in 1993, preserves the studio’s artistic heritage.

- [01] The DEFA Studio for Animated Films Dresden at Kesselsdorfer Straße 208 (1966) ©DIAF/Küssner, Schulz estate (Klaus Georgi)

- [02] The DEFA Studio for Animated Films with the new studio building under construction (1966) ©DIAF/Küssner, Schulz estate (Klaus Georgi)

- [03] The DEFA Studio for Animated Films in the 1980s ©DIAF

The animation studio of East German television

In 1956, one year after the founding of the DEFA studio in Dresden, a television-specific “puppet studio” is established in East Berlin at the East German broadcaster Deutscher Fernsehfunk (DFF), which makes a name for itself from November 22, 1959, primarily with its Our Little Sandman series (Unser Sandmännchen). However, it also produces animated commercials and music films, film satires for adults, and other animated films for children. As the official animation studio of East German television, it became the second-largest animation film producer in East Germany.

Unlike the Dresden studio, its Berlin counterpart changes locations more often. Initially located on the television grounds in Adlershof, it subsequently moves several times – to an abandoned dance school, a former cinema, and a former restaurant destination. The studio finds its final home in the former Lichtburg cinema on Hultschiner Damm in Mahlsdorf. There, it is able to expand considerably and combine several animation techniques under one roof. After the DFF was dissolved in 1991, the studio continues to exist in several locations for over a decade as “Sandmann Studio Trickfilm GmbH.” Today, other independent producers supply the TV stations in charge, rbb and MDR, with Sandmännchen episodes and bedtime stories Abendgrüße.

- [01] Ingeborg Blümel and Horst Walter animating the music film What can a yearning Sailor do? (lit., Was macht ein Seemann, wenn er Sehnsucht hat?, Peter Blümel, 1958) in the puppet studio of Deutscher Fernsehfunk in Michaelkirchstraße, East Berlin. ©Petzold Archive/Peter Blümel

- [02] The Mahlsdorf cinema “Lichtburg” on Hultschiner Damm in 1953. ©DDR-Postkarten-Museum/Postkartenverlag Kurt Mader

- [03] The “puppet ensemble” of the broadcaster’s own animation studio before 1975. ©Petzold Archive

Our Little Sandman and The Little Sandman

On November 22, 1959, East Berlin’s broadcaster Deutscher Fernsehfunk (DFF) launches the bedtime stories series with opening and closing sequences featuring the sandman figure Our Little Sandman (Unser Sandmännchen) – the sleep-inducing puppet created by director Gerhard Behrendt, who continuously takes on and develops the design with his collective. In West Germany, development is less straightforward. In 1962, director and producer Herbert K. Schulz is entrusted with the early evening TV series The Little Sandman (Das Sandmännchen). He is based in West Berlin with his own company, cinetrick, and is one of the few people there who practices puppet animation. Behrendt and Schulz both have their professional roots in the DEFA animation studio in Dresden. While the “East Sandman” is still celebrated as a successful character today, the production and broadcast of the “West Sandman” comes to a halt after the early death of Herbert K. Schulz in 1986.

- [01] Gerhard Behrendt “constructs” Our Little Sandman (Unser Sandmännchen) in the puppet studio of DFF in 1960. ©Petzold Archive

- [02] Mary Kames (left) and Ursula Schulz animate a space trip of Our Little Sandman to an orbital station (Gerhard Behrendt, 1970) in the puppet studio of DFF, with Horst Walter behind the camera. ©Petzold Archive

- [03] Herbert K. Schulz animates The Little Sandman (Das Sandmännchen) in West Berlin (mid-1970s). ©DIAF/Küssner, Schulz Estate

Aspects of animation dubbing in Dresden

A manually produced cartoon is created by recording individual frames. This means that original sounds cannot be used. Everything that can be heard in the film must be created separately. The models for this are reality and the animation’s “world of its own”. While many animated films rely solely on music and sound for their effect, others are additionally accompanied by commentary or dialogue.

Since its foundation, the DEFA Studio for Animated Films owns a sound department, and the sound stage is located in Dresden-Gittersee since 1960. A former restaurant destination, which was also used as a cinema and ballroom, is converted for this purpose. Music recordings, from small ensembles to full orchestras, take place in the large hall. Appropriate fixtures are provided for voice and sound recordings. The studio also maintains its own sound and noise archive, which is constantly being added to by Manfred Jähne.

The signal picked up by microphones goes through the mixing console and is recorded on 6.3 mm audio tape (also called “shoelace”). Then it’s transferred to perforated magnetic sound film (35 mm) or ‘split’ tape (17.5 mm). This audio material is “laid out” on the editing table parallel to the film. The same perforation ensures stable synchronization of image and sound. At the end of the sound recordings, the mix is created: sounds such as speech, noises, and music, which are stored separately on magnetic films, are adjusted and coordinated with each other using the mixing console. This is a tremendous technical challenge. While a projector plays the film, the individual tape decks transmit all sounds to the mixing console in sync with the images. Another tape machine records the finished mixed sound. This process requires an internal power supply with a stable AC frequency of 50 Hz. The mixed sound is then exposed as an optical soundtrack on 35 mm cinema film in the film laboratory.

- [01] Music recordings for the film Why Everybody Possesses Some Wisdom (Warum jeder ein Körnchen Weisheit besitzt, Bruno J. Böttge, 1959) ©DIAF/Böttge estate

- [02] Editor Renate Ritter “attaching” the sound material to the film ©DIAF

- [03] Edwin Ruprecht in front of the “Perfoläufer” (magnetic sound players) in the Gittersee sound studio ©DIAF

When dubbing animated films, the DEFA studio can draw on two processes and inventions that are unique worldwide: the impulse process and the Subharchord instrument

The impulse process

When animated characters are supposed to play music or dance, their movements must follow the beat and interpret the melody. Even the smallest deviations destroy the illusion of a life of their own. It is common practice to record the relevant musical passages before filming begins and to count them out as optical sound. This was cumbersome and expensive. Take, for example, the film Squirrel Brushy Ear (lit., Eichhörnchen Pinselohr) by Bruno J. Böttge (music: Conny Odd, 1962). Addy Kurth conducts the music recording. While counting, he notices that, apart from minor deviations, the quarter notes are twelve film frames long. This gives rise to the idea of calculating a timetable based on the score. Kurth chooses 24 frames for the half note, twelve for the quarter note, six for the eighth note, and so on. A comparison with the recorded music confirms this. Shortly thereafter, he presents his “impulse method”: The score is counted out. For the music recording, all musicians are given headphones with beeps corresponding to the beat. To generate the impulses, Addy Kurth and master mechanic Günter Steinigen construct an adjustable “impulse generator.”

The Subharchord

At the end of the 1950s, the Rundfunktechnisches Zentralamt (central office for radio technology, RFZ) of the GDR develops the Subharchord. With this sound generator, noises and sounds can be produced purely electronically. Addy Kurth accompanies this process as a musical consultant. He is now employed as a music dramaturge at the Dresden animation studio. He advises composers and directors on all questions of sound design. This includes Günter Rätz for the wireframe film The Race (Der Wettlauf). Kurth suggested setting the short film to music using the Subharchord. He developed the concept and wrote a complex score. The result is a novel artificial soundscape that contributes significantly to the film’s success. The RFZ orders a small series of the device to be built. One of them is purchased by the Dresden-Gittersee recording studio. It is used to generate special sounds until the studio closes. Since the Subharchord has no internal memory, it is rendered superfluous by the keyboard.

- [05] At the RFZ Berlin during the recording of the music for The Race (Der Wettlauf) on the stationary Subharchord on May 17, 1962: The picture shows, among others, director Günter Rätz (left) and composer Addy Kurth (third from left). ©DIAF/Gerhard Steinke

- [06] Addy Kurth at the mobile Subharchord, 1960s. ©DIAF

Animation unit

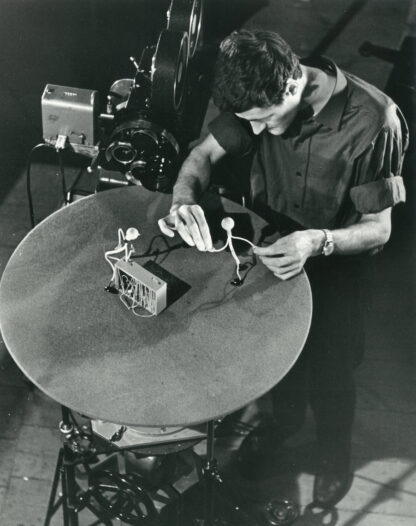

The animation unit from Richard Crass, West Berlin, consists of a recording table with a stop-motion camera for 35 mm film mounted above it. The animation table can be used to transfer two-dimensional artwork such as photos, graphics, or titles onto film. It is also possible to produce cut-out and drawn-animated films phase by phase. The artwork is usually illuminated evenly from above, silhouettes also from below. The camera can be moved up and down to simulate zooms. The table itself can be moved in two axes, which allows for (even diagonal) tracking shots. Camera movements can be precisely controlled remotely via the computer control system installed in 1984.

The animation table can be dated around 1960. Its first owner is the West Berlin-based Manfred Durniok Filmproduktion. In 1983, the equipment is acquired by Jutta and Dieter Parnitzke from PANs Studio West Berlin. It is initially used to animate film titles, then commercials. The later owners of the company, Aygün and Peter Völker, donate the animation table, camera, and computer control system to the DIAF in 2013.

The animation table could be operated while standing or sitting. In contrast, the animation tables at the DEFA Studio for Animated Films could only be used for animation while standing.

Computer animation

As with manual animation, the aim of computer animation is to create movements that do not exist in reality and hence cannot be recorded as live-action. Human characteristics and behaviors are made visible by transferring them to objects. Two prerequisites are necessary for the development of computer animation:

- the electronic storage and reproduction of image and acoustic information,

- the use of binary, digital codes instead of analog electronic signals.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the first analog “video graphics” were created by manipulating TV and video images. Such electronically generated visual results, such as patterns, distortions, and deformations, already represent simple, mostly abstract “animations” and can be combined with acoustic effects. Analog video and computer-generated graphics developed simultaneously, driven by the gaming industry. Computer graphics are an important precursor to today’s digital animation. Both work with binary number codes. They thus represent all image and sound information “discretely” and are based on digital programs, algorithms, and scripts. The former “grain” of photochemically produced film and the bright spot on the screen become pixels.

In the age of digitalization, there are two ways to create animated films:

- computer-assisted manual animation and

- computer-generated digital animation.

The simplest practice of computer-assisted manual animation is the use of digital cameras in the “filming process.” The individual phases are captured as separate photos and then combined into a film sequence on the computer. In drawn-animation, however, the manually created main phase drawings can be scanned and special software complements the intermediate phases and does the colouring. In cut-out or silhouette animation, the characters can be animated without backgrounds. The scenery is then digitally imported using “compositing.” A wide variety of variations and combinations are possible here.

In fully “computer-generated imagery” (CGI), all sequences are digitally designed and animated exclusively on the computer using “keyframes” and a variety of special software. While 2D animation is drawn digitally with special pens and tablets, spatial animation requires models or real people. They are scanned as mathematical spaces, as three-dimensional coordinate systems, and entered into the data universe, where they are further processed by the computer. However, in 3D computer animation, characters, sets, and props are also constructed entirely within the corresponding software using polygons. Computer animation can design movements very precisely, enabling subtle expressions that are particularly evident in facial expressions and speech.

Computers and artifacts

In digital animation, direct haptic-tactile interaction with physical material is reduced or eliminated altogether. As a result, there are hardly any “tangible” artifacts left as “by-products” of animated film production. Wonderful coincidences! “Original” drawings, transparencies, or puppets as unique exhibition objects with an aura of authenticity no longer exist; at best, there are drafts or sketches. Playable characters or colored drawing phases exist only as a huge collection of bits in the computer. These are not even suitable as “non-fungible tokens” (NFTs). On the other hand, a huge market is growing for digitally created merchandising figures from popular animated films, brought to life using 3D printers.

Lina Walde and Alma Weber are guests of the DIAF as “artists in residence” in 2024 and are developing the interdisciplinary project A Petticoat. At this time, both artists have already produced the digitally animated short film Dessert Critter (Wüstentier, 2023). For this film, Lina Walde still creates character designs with felt-tip pens as cartoon templates. A Petticoat represents an experimental intertwining of digital animation with texts by the poet Gertrude Stein. With music, the work becomes “expanded animation” in the accompanying live performance. The animation, which is generated solely on a computer, can only be presented as artifacts, as “digital exhibits,” for example in the form of Riso prints that can be produced as often as desired. This raises the question of how to handle digital animations in the archival practice on the one hand and the exhibitable nature of artifacts that do not actually exist physically on the other. Or to put it another way: In the age of digital reproducibility of exhibits, are exhibitions of animated films even possible anymore?